Picked up this album from 1973 in the back room at Rockaway probably twenty some years ago. Sale day and everything in that room was 75% off and nothing had been over three bucks anyway. This was the nadir of vinyl, everyone was buying CDs and most records weren’t worth much of anything anymore. Those were good days. I’d go full nerd in there, walk out with a stack of records for less than $50. Jazz to die for, nearly all of it mint or unopened. Rock albums people now pay ridiculous money for. Country they couldn’t give away (I remember getting a whole stack of classic Buck Owens in flawless condition for less than a buck a piece). And all kinds of music from all over the world. When records are under a buck you really can’t lose buying whatever. This was one of those. Probably paid six bits for it, unopened. I had never heard it, and his name was only vaguely and very distantly a memory and I had no idea from when or where or how. Later at home I put it on the turntable. This tune caught my ear. Listened to it again. Again. The liner notes gave an interesting backstory, how he’d lived in Liberia for a couple years and this was a conversation he’d heard on the local bus, hence “Overheard”. I put it aside and played some other records, then later went back and played the tune again. And again. And again again. I bet I listened to it—just this song—a dozen times in a couple days. And I just now listened to it now three times in a quick row. Weird how some songs get into your ear and under your skin like that, and you find’ll yourself hearing it from memory at odd times forever after, and have no idea why.

Category Archives: Music

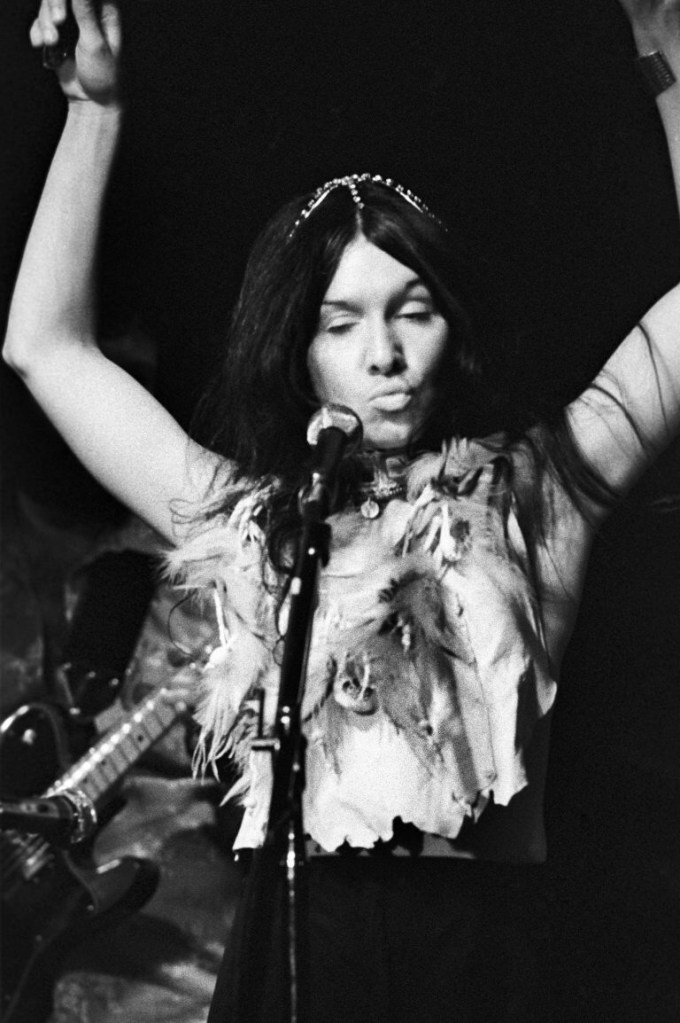

Buffy Saint-Marie again

Buffy Sainte-Marie off somewhere at the Bottom Line in 1974.

Though always my favorite of the singer songwriters, it’s funny to see what a challenge she proved to photographers who almost invariably failed to capture her intensity. It’s a shame, really, because in the days before video and online performances, photographs and vinyl were the only way most people ever got to experience a musician. Good photographs could make a legend, to this day we tend to recognize the artists who photographed well. Buffy Sainte-Marie was perhaps a bit beyond what photographers could see then, not that you could blame them, publicity and stereotypes were all about wind blown hippies or Joan Baez, and Buffy was neither. Still, photographer Waring Abbot caught a glimpse of something here on a spring night in New York City in 1974.

Vera Lynn

(June 2020)

103? I had no idea Vera Lynn hadn’t been long gone when people began writing tributes to her on Facebook. You just automatically associate her with the Blitz in WW2, Londoners traipsing down the long stairs underground into the Underground to wait out another night of Luftwaffe bombing and singing her hit We’ll Meet Again. It was to the Brits what White Christmas and Over the Rainbow were to Americans. You know those two, but Americans will likely remember We’ll Meet Again only from the closing shots of Dr. Strangelove, Vera Lynn’s voice over one nuclear explosion after another. The historical irony is lost on most viewers now, though, the Battle of Britain was eight decades ago. But it’s still a nice song, with a chorus that hangs with you a long time. Her recording of it, perfectly timed in 1939 as the men were mobilizing for war again, was a sweet delicate little thing, a little frail even, with a faintly ridiculous solo on one of those organs you’d hear in 1940’s soap operas. Within a year or two the song had swelled into a vast voiced thing, Vera singing along with hundreds of voices, whether civilians in bomb shelters or men in uniform, as in the movie clip below, and I suspect this is the arrangement many of her British mourners remember, and I hope they’ll forgive any of my inaccuracies here. Rest In Peace, Vera Lynn.

A long time gone

Some blistering guitar work in this linked video by Mike Bloomfield with the Electric Flag at the Monterey Pop Festival. The Flag, alas, were one of the acts that didn’t make it into the movie, which is a shame as Bloomfield was at the top of his game. But then the Electric Flag not making director Pennebaker’s final cut was really just another in the long line of missteps and misfortunes, mostly self-inflicted, that has left Mike Bloomfield perhaps the most forgotten guitar hero of them all. Indeed so forgotten that it’s startling to hear him speak in this clip from the Newport Folk Festival (about 3:20 in, just past Son House) because unlike his now legendary sixties guitar hero brethren, almost none of us has ever heard him speak. So dig his rap, the rushes of words, fragments of sentences, full of beatnik speak and musician jive and sounding incredibly like Jimi Hendrix, actually, whose voice we all have memorized. It must have been the way serious young players talked in the joints and road houses and cafes on the circuit in the early-mid sixties, where both Mike Bloomfield and Jimi learned their trade. And though some of you, perhaps even most of you, might not recognize Mike Bloomfield by name, you definitely know his sound–that’s him on Dylan’s Like A Rolling Stone, indeed all over Highway 61 Revisited, and that was him raising hell with Dylan at Newport. The second half of the sixties was an amazing period for Mike Bloomfield–Dylan, Paul Butterfield (East-West was one of the rock’n’roll game changers back then), The Electric Flag, Super Session–but he disappeared up his arm in the seventies and ceased to be entirely before the eighties even got started. A long time comin’ is a long time gone.

Penultimate Sunday at Cafe NELA

I don’t know how many hours all these very creative types—some musicians, a writer, a couple artists, maybe some others—had settled in around a beat up table in an assortment of abandoned chairs at the very bottom of the Cafe NELA patio. Either gravity or our careers had left us there because you couldn’t get any lower than that table. We sat there drinking and smoking and laughing way too loud, the jokes were terrible and the insults mean and the stories were always old and sometimes true. Far nicer people than us gave us a wide circle, like plump eating fish warily eyeing a circle of sharks. Sometimes one would foolishly come too close and be devoured, chomp, in a swirl of cackles and humiliation. It was all rather merciless and totally enjoyable and we sat there for hours laughing and basking in our asshole exceptionalism. We knew we were it. We knew it did not get any lower than us. More dumb jokes, each more offensive than the last. Some bass players have no pride at all. Eventually three grown men were doing Jackie Mason impressions at the same time, though not quite in harmony. I’d never heard three bad Jackie Mason impressions at the same time. Probably never will again. Pipes went round. Holy vodka in a water bottle, Batman. Even friends were abandoning us by now. The Jackie Mason was getting weird, the sculptress was getting dangerously out there. We were starting to peak on our own delicious high. This is what I’m gonna miss, my painter buddy said, this. You can see music anywhere, he said, but this…. He gestured it in water colors, I saw it in words. This, he said, this is the life.

Long, Long Time

Linda Ronstadt’s Long, Long Time must have been a huge hit in LA in 1970 because you’d hear it regularly on the local FM stations for years. All the teenage boys would freeze and listen and sigh. I hadn’t heard it in a while, and maybe the effect is accentuated on this iPhone, but why did producer Elliott Mazer bury her in the strings? Not right away. It’s all Linda Ronstadt for a minute, almost like Kitty Wells, and you’re hooked. But from then on Mazer starts piling strings on by the regiment full, and Linda’s battling to be heard over the arrangements. They’re everywhere, these charts full of lush baroque things growing like triffids, filling every available space. At one point the harpsichord is louder than she is. It’s almost like a Phil Spector thing, Tina Turner batting Phil’s Wagnerian demons on River Deep, Mountain High. Linda finally wins in the end, though, even if the strings and that strutting harpsichordist get to do their dirge thing for a bit too long after her vocal fades, though I suppose the logic of the arrangement demanded it. These things require patience. At last they’re done. That’s a wrap, Mazer said, and maybe someone went to chuck a few too many cellos and violas into the Cumberland. Anyway, a lovely tune.

An appallingly bad cover photo. Somebody should have been fired.

Chimera

Flipped on the radio and it’s Loan Me A Dime and talk about nostalgia, like a foggy Sunday morning in Isla Vista, or late night hippie sounds on KNAC out of Long Beach way back when. This was the ultimate long playing FM song for a while, Boz Scaggs before Low Down, still in boots and jeans and a beat up cowboy hat. It starts out slow, just this side of a dirge, but builds into a rollicking piano pumping blues, and Duane Allman laying down lick after lick of the meanest Muscle Shoals lead guitar you ever heard for several exuberant minutes. You hope it never ends. But it does, finally, after thirteen minutes, fading out with the band still rollicking and Duane Allman still on fire, and you can’t believe you were lucky enough to hear it again because almost nobody actually had the album. It was just this amazing thing you heard on the radio, and it was hippie long, long enough to smoke a whole joint to. A big bomber joint even. And if the deejay then spun Voodoo Chile or Low Spark or that long medley off Abbey Road you know he’d been out back smoking that joint. But that was nearly half a century ago. This deejay today segued (if you can call it that) into a coked out Eagles cut and ruined everything. The vibe was gone, poof, instantly. Life In the Fast Lane. What’s the opposite of nostalgia? Because that’s what this was. Memories of being stuck in the mid seventies and looking like I’d never get out.

Trout Mask Replica

It came out in 1969 and even though I’d heard of it for years, I didn’t actually hear Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica until much, much later: 1978. Nine years late. Talk about uncool, uneducated, and unhip. Still, it immediately had a huge impact on me. Not just the mind blowing music (“Pena” remains the strangest piece of music I’ve ever heard), but the stunning imagery in the lyrics, which shaped my own prose (especially “Bill’s Corpse” for some reason I could not begin to explain). People read my stuff and assume I’ve read James Joyce but I never have, what they’re hearing is Don Van Vliet. But perhaps most surreal to me now is the fact that four decades have transpired since this now five decades old album finally connected with my gray matter. It was on the third spin in perhaps as many days and it still eluded me until half way through “Hobo Chang Ba” I got it. Hobo Chang Ba, the Captain groaned, Hobo Chang Ba, and suddenly all was clear. What exactly made it so clear I do not know, but suddenly the frantic clattering music made perfect sense. It still does, most of my lifetime later. Forty years can make a man’s eyes, a Beefheart fan’s eyes, flow out water, salt water.

Put it where you want it

Great. Put It Where You Want it again. It’s been days now. I deliberately left a big stack of LPs of all kinds right in front of the turntable and what do I do? Just drop the tone arm on the record already on there. You try to take it off again after hearing those first descending chords on that way groovy electric piano. Then in comes the way funky guitar picking out the single noted melody at a mellow strut. This has been in my head since it was a hit on an AM station in funky town Anaheim during Richard Nixon’s first term. I lived in funkier town Brea but the station was in Anaheim. KEZY. They spun the tune on the hour for a week or two and it dug itself in so deep in my brain it even survived all the seizures later. And I’m gonna take it off now? I’m reliving my virgin youth. I was so young I didn’t even know the title was a double entendre. Irony is one of the last things to develop in the human brain, you know. At some point maybe 40 thousand years ago metaphors happened and with them the capacity for irony and Homo sapiens became insufferable. No wonder Neanderthals became extinct. Imagine sharing a cave with us, let alone DNA. That’s some brow ridge you got there honey. You could recite Shakespeare from that thing. Forty millennia later I’m thirteen and digging Put It Where You Want It like a clueless Neanderthal, wiggling my little white butt and humming along. The deejay comes on and says something filthy. I can’t tell. This is how civilization began. Cue the Also Sprach Zarathustra. Or maybe just flip the Crusaders album over to the B side. Or D side. Whatever. It’s a double album, and those were confusing times.

About Lester Bangs

Astral Weeks, insofar as it can be pinned down, is a record about people stunned by life, completely overwhelmed, stalled in their skins, their ages and selves, paralyzed by the enormity of what in one moment of vision they can comprehend. It is a precious and terrible gift, born of a terrible truth, because what they see is both infinitely beautiful and terminally horrifying: the unlimited human ability to create or destroy, according to whim. It’s no Eastern mystic or psychedelic vision of the emerald beyond, nor is it some Baudelairean perception of the beauty of sleaze and grotesquerie. Maybe what it boils down to is one moment’s knowledge of the miracle of life, with its inevitable concomitant, a vertiginous glimpse of the capacity to be hurt, and the capacity to inflict that hurt.

Lester Bangs, Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung

That Astral Weeks review is awfully pretty, gorgeous even. Too bad it’s complete horseshit. It has nothing to do with what the album sounds like and everything to do with Lester Bangs. Not that Lester Bangs wasn’t an interesting guy, but if you’re reviewing a record you should leave yourself at the door. I don’t care how many English classes you’ve had or if you’ve read Baudelaire or can do more acid that Philip K Dick, I just want to know what the album sounds like. The vast majority of music critics seemed to ignore that idea. Lots of pretty words that don’t give you a clue about what the music actually sounds like. If you want to write about yourself, write your memoirs. If you’re going to review an album, let the music do the talking. And if you can’t do that in prose, you’re in the wrong business. Because when you write about music, the only thing that matters is the music. You the critic don’t matter at all.

Here’s a rule of thumb…if you’ve completed a review and it’s one of the best things you’ve ever written in your life, dump it. You probably wrote about yourself.

(Comments posted to a New Yorker piece about Lester Bangs, 8-30-2012)