One of my very favorite moments from The Last Waltz, with Robbie Robertson and Eric Clapton out front with The Band on Clapton’s live standby Further On Up The Road. Clapton’s in fine form but far too polite an Englishman to engage in a tawdry North American style cutting contest, but Robbie, raised in gritty roadhouses on both sides of the border, doesn’t know any other way and goes for the jugular, blood all over the floor by the time he finishes. Eric grins a surrender and follows up with a fine solo but never tries to outdo Robbie, whose show it is afterall. Rock’n’roll can be so polite. In real jazz and old R&B it could have been Robertson’s deathbed solo and the other cat would have tried to bury him anyway, no mercy, no quarter. I always thought it a shame that Clapton didn’t come back with a solo to make this a cutting contest to the death, back and forth, each of them throwing everything they had into topping the other motherfucker’s solo till, exhausted, one or the other gave in, humiliated. I’ve watched saxophone players do that and you can see the moment one of them, laughing and vanquished, gives in. It’s macho to the core. Exhilarating. But Eric was a nice guy, and it was a bittersweet event in a San Francisco hall full of faded peace and love hippies and he let Robbie have this one in a classic Robbie Robertson explosion of rockabilly and blues licks.

Category Archives: Psychedelic

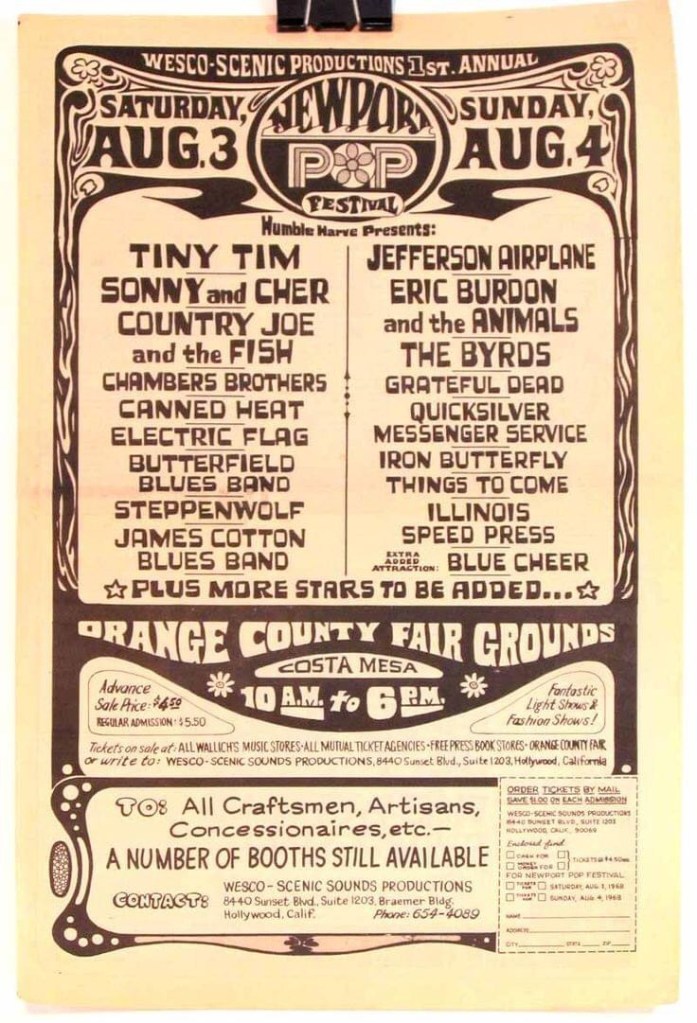

Unrecorded and unfilmed

Hot damn. At the Orange County Fairgrounds, no less. The fact that this, and similar festivals in ‘67, ‘68, and ‘69 were not filmed and recorded is I suppose because the concept of doing so was so new. The technology was new and the people with the necessary technical skills to film and record live music in an anarchic festival setting were few and far between. Financial backing was very difficult to obtain (be honest, would you invest in a festival concert film?) No one even knew what you could do with a concert film—the huge success of “Woodstock” in 1970 was unimaginable. And then there was the fact that a live recording that would have to be a double or triple record, and the record industry was just trying to get used to double albums by single bands in 1968, let alone featuring a dozen bands. And the record industry was right to be skeptical, most of the festival live albums didn’t sell well, not even Woodstock 2. The few that were released wound up in the cut out bins for a quarter (about two bucks in today’s money.) So nearly all of the dozens or scores of huge festivals didn’t get filmed and released. Most weren’t even audio recorded. Bummer. Hell, even jazz festivals were under recorded and rarely filmed, and jazz fans were rarely naked or tripping or fucking at those (well, not as much anyway.) What an archaic anarchic time that was. A stone age stoned age.

Terry Reid

Just love this, Terry Reid—I so dig his voice and guitar playing, both unique as hell—performing ”Dean” at Glastonbury Fayre in 1971. He’s got David Lindley (Kaleidoscope had called it a day in 1970), and that’s Alan White laying down an incredibly loose unYes groove on the traps, and just as the tune is ending a thoroughly psychedelicized Linda Lewis wanders up on stage and carries it along tripping another four minutes (of which she remembers nothing, she confessed later, but she did remember dancing with a tree.) I never did understand why Terry Reid never made it, I suppose his thing was just a little too off center, his groove a little too serpentine and scratchy, even for those days. Oh well, rock’n’roll. This is from the Glastonbury Fayre documentary, which if not Nicholas Roeg’s finest moment is one of those incredibly hippie things with lots of naked muddy way out people way out on acid, and lots of way out great music. Even extremely way out music. Apparently they never got round to tell us who’s playing what, not even band names, which will drive you slightly nuts, but subtities are for squares anyway.

Alas, in the year since writing this, the clip from Glastonbury Fayre has been removed from YouTube, and hence I never posted this. It seemed a shame to throw out such a nice little piece, though, and now someone has posted the audio recording from the Glastonbury documentary so here that clip is. The still is from the film. I heartily recommend purchasing a copy of the film, though. It’s no Woodstock as far as production quality goes, but it still a pretty amazing document.

John Sebastian

The 400,000 people at Woodstock were still antsy, high and loud after Santana’s starmaking performance, but the crew didn’t dare put another electric band on stage till the weather settled down. That upstate New York weather. John Sebastian was hanging around back stage just tripping on the acid he’d dosed somehow, when Chip Monck—that’s his voice, introducing him—told him he needed to play. John, way too buzzed, said no. He hadn’t even brought a guitar with him. Not even an autoharp. Someone handed him Tim Hardin’s guitar. (Tim didn’t make the cut for the movie so his guitar is as close as he got to Woodstock movie stardom that day.) Darling Be Home Soon is one of Lovin’ Spoonful’s classics, a hit you don’t hear on the classic rock stations, one of those earnest folkie things, like a Simon and Garfunkel tune, overly arranged, a loud horn section, perfect grammar and sweet melody, rhyming dawdled with toddled and with an unforgettable hook in the melody. He begins the song and the crowd cheers, like they’d been hoping that he’d sing it, and within a few seconds the vast throng is hushed, swaying slightly with the rhythm, quiet as a church, listening to the words, just John Sebastian and a guitar and a melody and the 400,000 people not making a sound. Go, he sings, and beat your crazy heads against the sky, the melody somehow soaring like a big rock band, try and see beyond the houses and your eyes, it’s OK to shoot the moon, which a half century later sounds a little clumsy, but in the summer of 1969 in a sea of 400,000 heads and hippies it must’ve sounded like pure poetry, and it wasn’t until he sang the last few words that you can hear the sounds of 400,000 stoned people again, their cheers like waves rolling in from the deep to inundate the stage.

Spirit

Just to age myself even more, I got that Spirit box set which includes the first four albums plus another album and a soundtracks and singles, outtakes and whatever else they could squeeze on five discs. Hot damn this shit is good. Always loved these guys. Poor bastards were not big enough to be really popular but too big to be considered a cult band. Spirit were the band whose manager cancelled their Woodstock appearance so they could play a high school auditorium in nearby Binghamton. Well, they got paid for playing Binghamton, there was that. But imagine playing a set to a few hundred people when you were could have been playing for hundreds of thousands a helicopter flight away. It shall be.

Shootout at the Fantasy Factory

Hearing this tune always reminds me of my pre-punk rock life. If you’re old enough you had a completely different existence before you first heard the Ramones or Sex Pistols. We liked lots of hippie music and had lots of hippie thoughts, though I can’t remember most of them. Anyway, I used to have this album. It was the Traffic album that had what, three songs? Maybe four or five, I can’t remember. Apparently all the touring and drugs was taking its toll on the songwriting. Sometimes I feel so uninspired, Stevie sang in his most mournful rock star voice, sometimes I feel like giving up. Subtle. And then there was Roll Right Stones, which I always assumed was another of those Winwood way cool English jazz hippieisms I never could figure out—the lyrics to Low Spark of High Heeled Boys on the previous record took me years of exegesis. Turns out the Roll Right Stones are actually a trio of megalithic monuments out in the English countryside dating back to the Neolithic. We didn’t have Wikipedia in the seventies, so I just figured it meant cool or groovy or keep on truckin or whatever. I wasn’t the brightest kid. Whatever the title means, Roll Right Stones does eventually cook, even wail a bit, but it felt like half a Dead show before you got there. The fucker takes up about half the record, not so much filling out side 1 as it did slowly ooze over it, filling in just enough grooves to please the record company. OK, maybe that was harsh. But it is a long stoned song. The title track was great, though, and kinda weird. It was the Traffic tune that people who loved Baby’s On Fire liked. You’d hear the tune a lot on FM for a while, though I haven’t heard it in years. Which is odd because I still listen to Traffic pretty regularly, and still love Steve Winwood’s voice, even if you can’t tell by the attitude above. I wrote most of this some time ago, I think during that nasty heat wave, hence the grumpiness. It happens.

Oh, Rebop Kwaku Baah. Almost as fun to write as it is to say. He cooks on the title cut. Rebop Kwaku Baah. That’s twice.

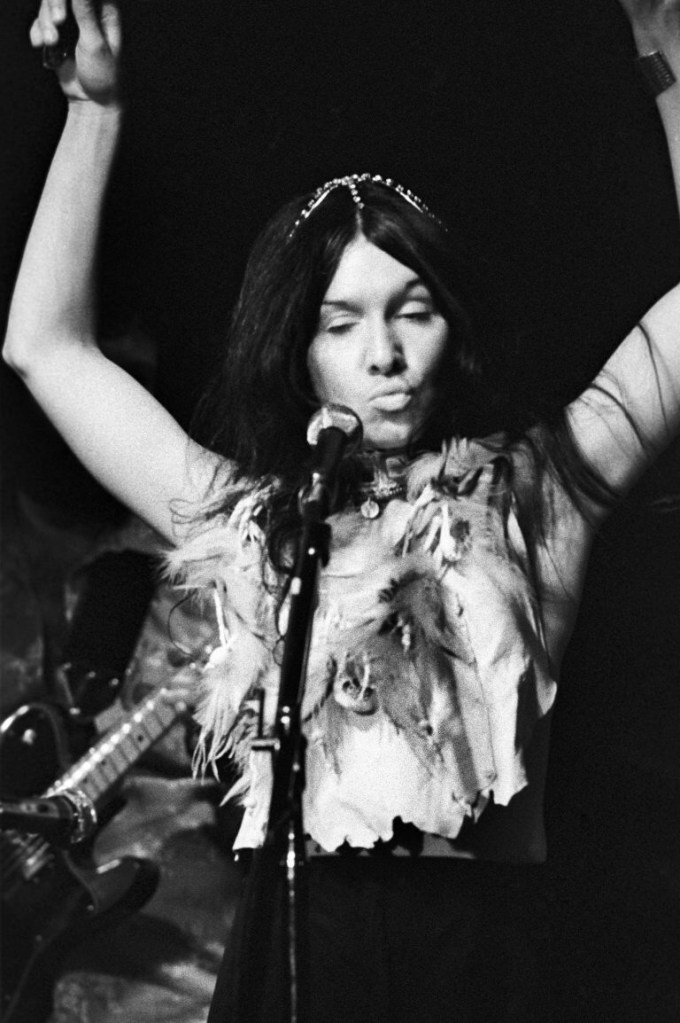

Buffy Saint-Marie again

Buffy Sainte-Marie off somewhere at the Bottom Line in 1974.

Though always my favorite of the singer songwriters, it’s funny to see what a challenge she proved to photographers who almost invariably failed to capture her intensity. It’s a shame, really, because in the days before video and online performances, photographs and vinyl were the only way most people ever got to experience a musician. Good photographs could make a legend, to this day we tend to recognize the artists who photographed well. Buffy Sainte-Marie was perhaps a bit beyond what photographers could see then, not that you could blame them, publicity and stereotypes were all about wind blown hippies or Joan Baez, and Buffy was neither. Still, photographer Waring Abbot caught a glimpse of something here on a spring night in New York City in 1974.

A long time gone

Some blistering guitar work in this linked video by Mike Bloomfield with the Electric Flag at the Monterey Pop Festival. The Flag, alas, were one of the acts that didn’t make it into the movie, which is a shame as Bloomfield was at the top of his game. But then the Electric Flag not making director Pennebaker’s final cut was really just another in the long line of missteps and misfortunes, mostly self-inflicted, that has left Mike Bloomfield perhaps the most forgotten guitar hero of them all. Indeed so forgotten that it’s startling to hear him speak in this clip from the Newport Folk Festival (about 3:20 in, just past Son House) because unlike his now legendary sixties guitar hero brethren, almost none of us has ever heard him speak. So dig his rap, the rushes of words, fragments of sentences, full of beatnik speak and musician jive and sounding incredibly like Jimi Hendrix, actually, whose voice we all have memorized. It must have been the way serious young players talked in the joints and road houses and cafes on the circuit in the early-mid sixties, where both Mike Bloomfield and Jimi learned their trade. And though some of you, perhaps even most of you, might not recognize Mike Bloomfield by name, you definitely know his sound–that’s him on Dylan’s Like A Rolling Stone, indeed all over Highway 61 Revisited, and that was him raising hell with Dylan at Newport. The second half of the sixties was an amazing period for Mike Bloomfield–Dylan, Paul Butterfield (East-West was one of the rock’n’roll game changers back then), The Electric Flag, Super Session–but he disappeared up his arm in the seventies and ceased to be entirely before the eighties even got started. A long time comin’ is a long time gone.

Trout Mask Replica

It came out in 1969 and even though I’d heard of it for years, I didn’t actually hear Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica until much, much later: 1978. Nine years late. Talk about uncool, uneducated, and unhip. Still, it immediately had a huge impact on me. Not just the mind blowing music (“Pena” remains the strangest piece of music I’ve ever heard), but the stunning imagery in the lyrics, which shaped my own prose (especially “Bill’s Corpse” for some reason I could not begin to explain). People read my stuff and assume I’ve read James Joyce but I never have, what they’re hearing is Don Van Vliet. But perhaps most surreal to me now is the fact that four decades have transpired since this now five decades old album finally connected with my gray matter. It was on the third spin in perhaps as many days and it still eluded me until half way through “Hobo Chang Ba” I got it. Hobo Chang Ba, the Captain groaned, Hobo Chang Ba, and suddenly all was clear. What exactly made it so clear I do not know, but suddenly the frantic clattering music made perfect sense. It still does, most of my lifetime later. Forty years can make a man’s eyes, a Beefheart fan’s eyes, flow out water, salt water.

Mitch’s sticks

Watching the end of Jimi Hendrix at Monterey and amid the smoking wreckage Mitch Mitchell rockets his sticks into the stunned stoned freaked and tripping crowd and every time I see it and (and I’ve seen it a hundred times) I think that I would have given anything to have been in that crowd and caught one of those sticks, it would still be my most treasured possession, that stick, even now, that half a century before had rolled across those toms with absolute abandon and bounced with loose wristed splats off the snare and set the cymbals roiling and splashing and crashing with Jimi’s every move and sound and look and thought. Airborne for only a second or two, the sticks disappear into offstage darkness, first the one, then the other and Mitch, laughing, steps out of view. I turn off the TV right then, before the interviews begin and reduce the music to history, and I wonder again about those sticks.